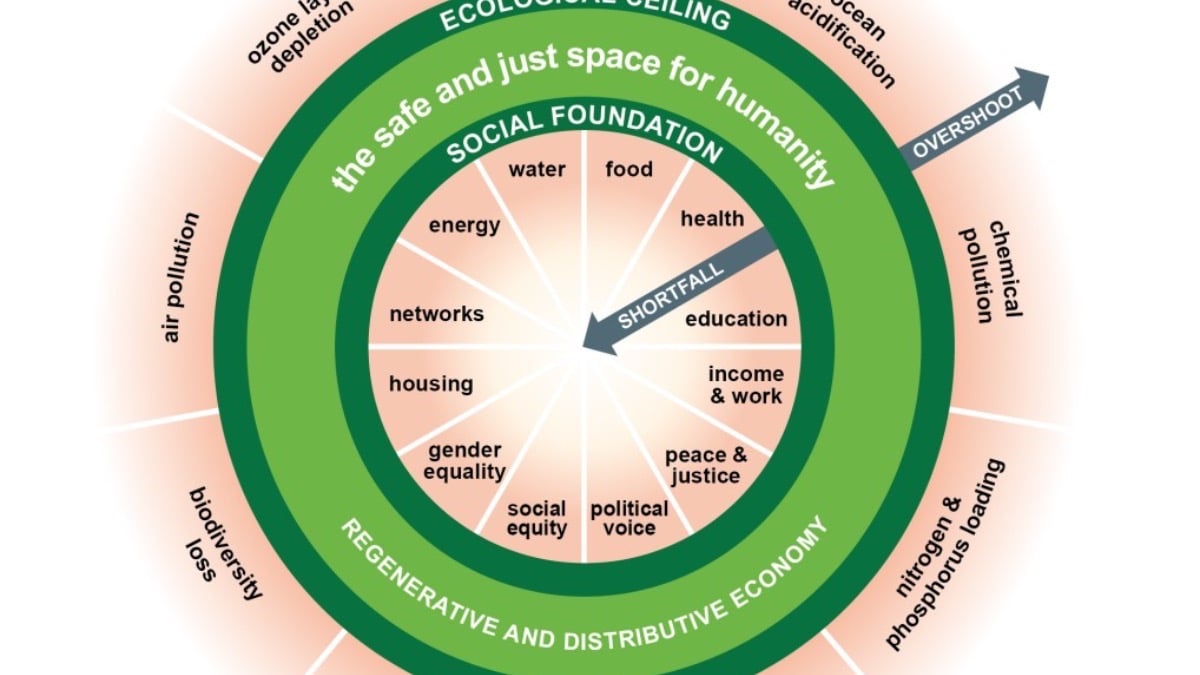

Sustainability is a term we encounter frequently today, yet its true meaning often escapes clear definition. At its heart, sustainability revolves around creating conditions that allow humanity to thrive indefinitely without depleting resources for future generations. The foundational definition by the Brundtland Commission in 1987 describes sustainable development as meeting our current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs, emphasizing the importance of intergenerational equity and social justice. Economist Herman Daly further deepened our understanding, outlining key principles such as staying within the earth’s carrying capacity, enhancing efficiency rather than mere resource throughput, and ensuring renewable resources aren’t depleted beyond recovery. This differentiation introduces us to the concept of weak versus strong sustainability. Weak sustainability presumes natural capital—our ecosystems and natural resources—can be replaced by manufactured capital, such as infrastructure and technology. Conversely, strong sustainability insists that natural capital is irreplaceable because ecosystems perform essential functions impossible for manufactured alternatives to replicate—such as purifying air and water, stabilizing climate, and supporting biodiversity. Kate Raworth’s “Donut Economics” visualizes sustainability as a balance between ecological ceilings and social foundations. She argues that humanity should strive to live within a safe and just space, avoiding environmental overshoot while simultaneously addressing basic human needs like health, education, housing, and equitable economic opportunities. The challenge lies in operating within these ecological and social boundaries, maintaining a regenerative economy that benefits everyone. Social issues, often overshadowed by environmental concerns, are equally critical. Poverty, equity, and human rights directly affect sustainability. Persistent inequalities, illustrated by global poverty, highlight the challenge: communities preoccupied with survival cannot prioritize environmental or long-term economic stability. For example, addressing global hunger through sustainable agriculture practices not only resolves immediate human needs but also secures environmental and economic sustainability by promoting local, low-carbon food systems. Meanwhile, the environment remains central to sustainability concerns, primarily driven by human-induced climate change and its cascading impacts. Increasing greenhouse gas emissions since the Industrial Revolution have raised global temperatures, causing sea-level rise, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, and a host of weather-related disasters. The exponential growth of population and resource consumption compounds these challenges, pushing Earth’s natural systems to their breaking points—a scenario depicted vividly by concepts like “Limits to Growth” and “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Understanding these interconnected issues is fundamental for any sustainability professional, as they affect businesses, communities, and governmental policies alike. It is crucial for us, as current and future leaders, to promote solutions that acknowledge our ecological limits, value all forms of capital, and recognize that sustainable progress depends on balancing social, economic, and environmental priorities. Before moving to the first article takeaways, let’s highlight they key social, environmental, and economic issues which represents the building blocks of understanding sustainability and it’s related challenges and opportunities: Key Social issues: Basic Human Needs Equity Human rights Justice: Social and Environmental Better Life Index Sustainable Agriculture and Reducing Hunger Key Environmental Issues: Climate Change Decline of Natural Capital Unsustainable water use Key Economic issues: Setting Economic Priorities Sustainable Economic Models Sustainable Markets Key Takeaways: Sustainability involves meeting current needs without hindering future generations’ ability to do the same. Strong sustainability emphasizes preserving irreplaceable natural capital. Social issues like poverty and equity deeply intertwine with environmental and economic sustainability. Population growth and increased consumption are intensifying pressures on natural resources. Integrated solutions and systemic thinking are essential for real sustainability progress.

Copyright © 2025, takamol-eg. All rights reserved.